Six Standout Artists On Display at The Art Show 2020

Recap from ADAA: The Art Show // Park Avenue Armory // New York City

My phone died as I entered the Park Avenue Armory. With a moment to sit by the electrical outlet, under the dark wooden staircases and florid chandeliers, I remembered the first time I came to this cavernous and ever-transforming space. It was for a performance—I watched a Parisian ballerina so long and limber that I expected her body to snap in half with each arabesque.

On Sunday, March 1, the last day of the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA): The Art Show, performances were reserved for the art dealers—and as a director at PPOW stated, they all brought their A game. Given the proliferation of the art fair model and its reputation for being played out and inadequate, as well as exhausting for the arts workers who produce them, the handful of cancellations due to COVID-19 has felt like an overdue interruption to the global fair cycle, albeit under unfortunate circumstances with uncertain implications—emotional, economic, mortal, and otherwise. Admittedly though, seeing The Art Show felt worth the time and effort. Being out ahead of Armory week and stacked with heavy hitters, it positions itself as the leader. It feels approachable, even intimate, and the historic space sets the mood apart from warehouse fairs. What it lacks in risk, it makes up for in experience.

John Marin, Movement: Sea Played with Boat Motive, 1947

An artist frame accented by bits of driftwood and blue paint and hung on a fuchsia wall was the first small standout—I’m always looking for something special in the framing regard as it’s my day job, and though the canvas is full of rich architecture, I wouldn’t have noticed it otherwise. The artist, abstract painter John Marin (1870-1953), was a contemporary of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Milton Avery, and ostensibly even more popular. The dealer at Menconi + Schoelkopf surmises that the scale of his work, which never went far beyond 24 by 28 inches, may have contributed to his soft neglect by the canon. The story of neglect extends to his original frames, few of which remain intact as collectors have opted to replace them with sleeker options.

Untitled works by Martín Ramírez ca. 1960-63

Untitled works by Martín Ramírez ca. 1960-63

Ricco/Maresca is conducting a tour of Martín Ramírez (1895-1963), whose work I had only encountered on US postage stamps circa 2015. As a non-profit fundraiser who sent thank you notes daily, these stamps were far and away the best in the game. I coveted them. Ramírez used a repeated archway motif, creating shadowy arcades throughout many of his drawings. In looking at these portals or stages, spaces of suspense, silence, emptiness, we’re reminded that, “any artistic act is a sign whose possible meanings resist our interpretations and remain silent at the end”—especially since Ramírez left no writings about his work. The dealer encourages a both/and approach to looking at Ramírez: consider the context of his life as an immigrant from Jalisco, Mexico, an individual who experienced mental health challenges, and a worker who built railroads in California, alongside formal assessments of his singular style, palette, and composition.

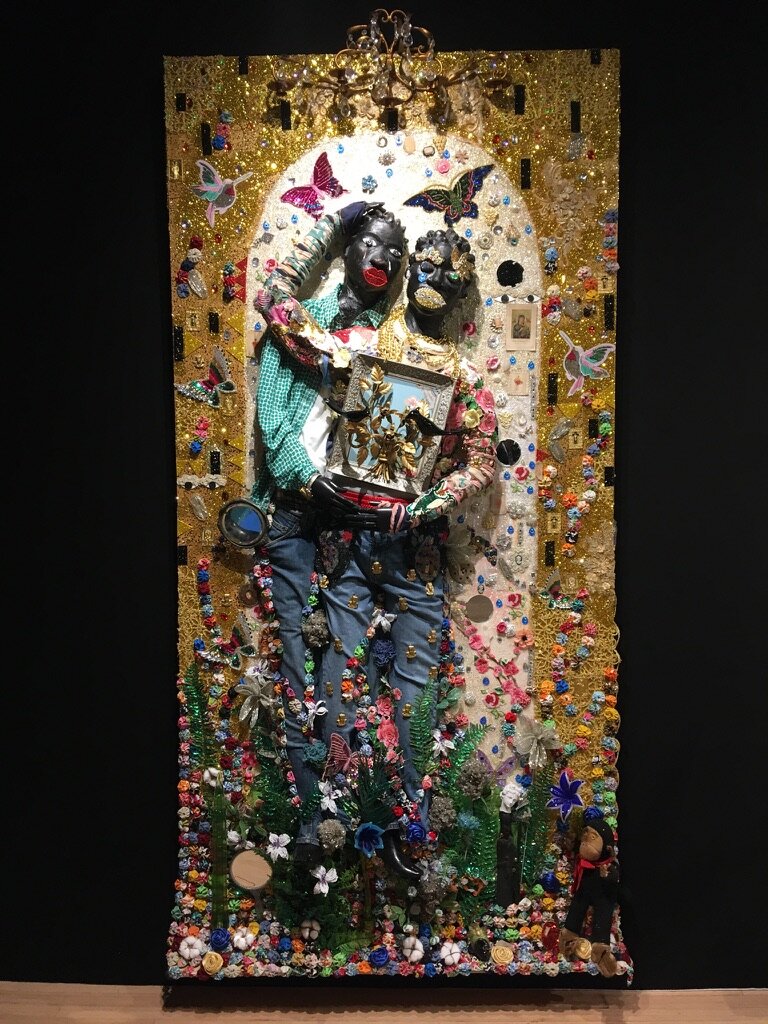

Vanessa German artwork with details, title unknown/unlisted online

Vanessa German artwork with details, title unknown/unlisted online

At Pavel Zoubok, Vanessa German’s (b. 1976, WI) lovingly rendered bodies summon racial, sexual, and social healing. This activist, performance artist, and poet from Pittsburgh sculpts what she calls her “tar babies,” clothes them, and layers them with an astounding assortment of found objects including mirrors, glitter, embroidery, religious iconography, and other thingamabobs. These sculptural portraits are loudly beckoning from afar and tender up close. In spending time with each life size figurine, you get the uncanny sense that you are actually getting to know another being—through conversation in addition to observation. The mirrors are the key.

Ramiro Gomez, Be Bold, 2020

Installation view with Installer 3, 2020

Ramiro Gomez (b. 1986, CA) is known for inserting clear, powerful sketches of domestic workers into glossy magazine spreads. At PPOW, he has brought us all into the scene, erecting life-size cardboard cutouts of arts workers on a ladder, cleaning the floor, placing a wall. The booth’s wall panels are not smoothed over and painted, but rather left as they’d been brought in, displaying echoes of fairs past—leftover wallpaper, bits of tape, drill holes, spackle, gaps—both an acknowledgement and an aestheticization of labor. We’re not worthy of Gomez’s caring and relentless focus on the invisible and undocumented labor that buoys all of our lives, but ever do we need it.

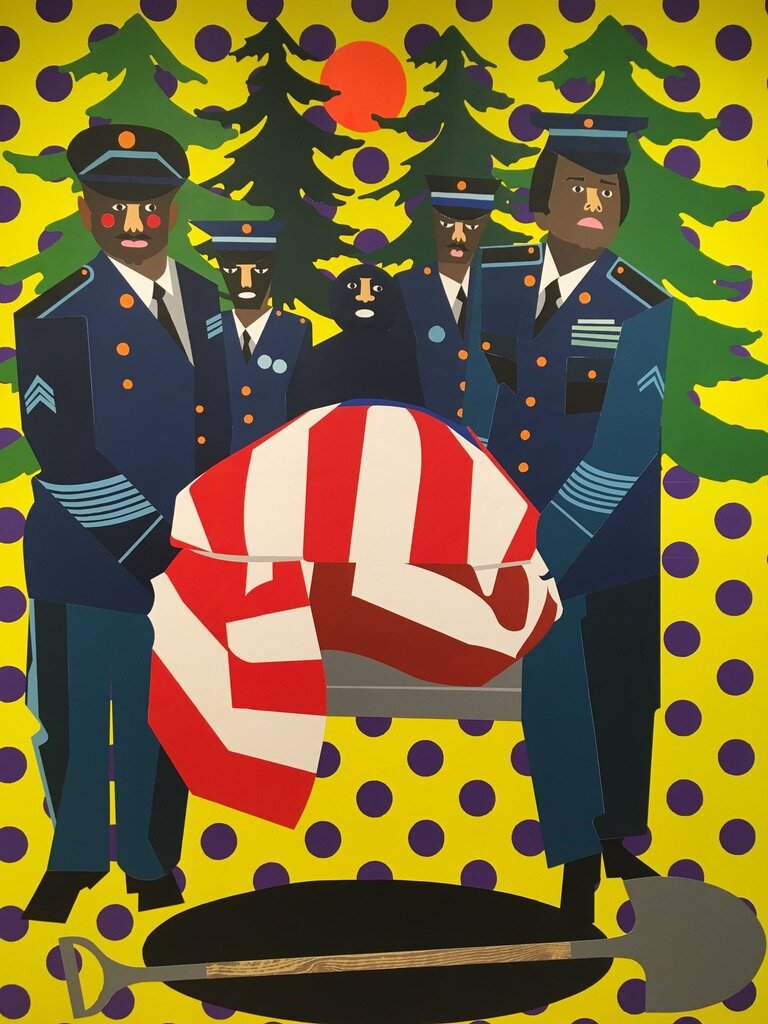

Nina Chanel Abney, House of Reps (detail), 2020

She Was a Real Trouper – Acts of Service, 2020

Nearby at Pace Prints, our entangled and embedded relationships with nationalism and consumerism are expertly layered in giant paper cuts by Nina Chanel Abney (b. 1982, IL). A black woman reading in bed is visually trapped between her Navajo weaving patterned wallpaper and an American flag duvet. A group of black American soldiers are pall-bearers walking toward a freshly dug cartoon burial pit. Each of these works tell us that decolonization is not a metaphor, while also selling for tens of thousands of dollars at an art fair attended by mostly white people (myself included) on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, the land of the Lenape people. Abney brings radiant color to our country’s dark, abiding truths.

Jordan Nassar, the sunset’s last rays, 2020 (above left), and the sun has set, 2020 (above right)

A presentation of Jordan Nassar’s (b. 1985, NY) work at James Cohan rounds out the best of the fair. Employing Palestinian tatreez, the matrilineally learned tradition of hand-embroidery, Nassar translates an antique dress on display at the center of the booth to a handful of surrounding canvases. By introducing landscape into pattern and leaving an abundance of blank space, he creates contemplations on land lost, remembered, and imagined, the perennial diasporic exercise. Nassar’s frames and display case, as well as the accompanying catalog produced entirely in Arabic, are exquisite.

Jordan Nassar catalog

One thing about the art fair model does cut through any opinion—the range and quantity of work brought together in one place makes the stars of them shine brighter. So long as the fairs persist, may they be as well produced as The Art Show. Bravo, dealers.

Did you attend The Art Show this year? Which artists stood out to you?

This article is by Sonja Roach. You can find more of her writing on art at @walkingaboutart.